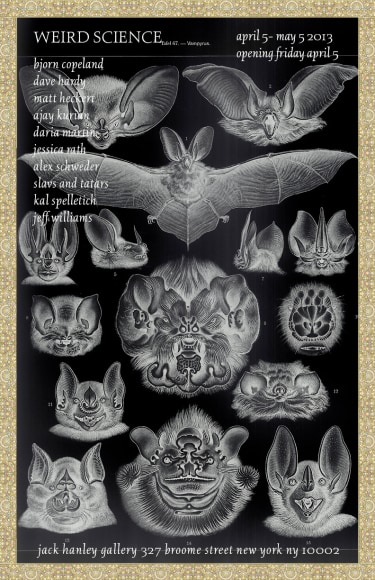

WEIRD SCIENCE

Bjorn Copeland

Dave Hardy

Matt Heckert

Ajay Kurian

Daria Martin

Jessica Rath

Alex Schweder

Slavs and Tatars

Kal Spelletich

Jeff Williams

April 5- May 5 2013

Opening: Friday April 5, 6-8 pm

‘Weird’ is a common go-to word to describe an artist’s work. Often this is because something relatively normal or naturalized is made weird through the lens of an artwork; or rather, its strangeness is exposed (every object, every idea, has its freak flag). An interesting thing happens when an artist points to science. A surprising or unexpected disposition of a process can come to the fore, or analytic methods channeled to explore aesthetic, political or philosophical areas. Within the scope of this exhibition, artists have included experiments in the natural or material world, or ethno-focused investigations that take for subject matter language, architecture, and social relations. In some ways, the first encodes a worldview, while the second decodes those that we have already. However, this distinction is in no way meant to over-simplify, and there is a shared commonality when man is the measurer.

Many of these investigations activate different and hidden modes of a familiar material or space. Dave Hardy uses everyday building supplies – foam, cement, glass – in massive conglomerates that are held together through gravity and tension. Ajay Kurian melts gummy bears, microwaves bars of Ivory soap to reveal the billowy insides, and textures paintings with crystallized sodium borate. Each of these elements has an anecdote. For instance, the preservative in the gelatin of a gummy bear keeps it from ever fully solidifying or breaking down. While interested in our ideas of the organic and synthetic, Kurian also has a way of leveling the playing field between the two. After all, “the things we tend to also tend to us”, and to forget this is to fall into an overly deterministic pattern of thinking.

Similarly, for Alex Schweder, the way in which one interacts with one’s living space, the “non-I that protects the I”, will help to define its parameters2. In fact, a playful or inventive change in behavior is as profound on the home as an addition to it. As part of his one-week performance for the show, Schweder will be offering free architectural advice on how to renovate the home through the addition of prescribed performances, some of which he has acted out in a series of accompanying photographs.

Conversely, our concepts and awareness of time and space are often inseparable from an immediate material reality. Before becoming part of a greater dialogue, Benjamin Whorf, a fire-inspector turned linguistic theorist, found time to be “patterned on the outer world”. Time is imagined in numbers, and the tongue “makes no distinction between numbers counted on entities and numbers that are simply ‘counting itself’”. It is quantified in “lumps, chunks, blocks”, substance and matter2. Jeff Williams’ works operate using two different but related time scales: a real-time change during the course of an exhibition, and an implied long-term transformation that is only glimpsed at during the show.

Conservation Fountain sprays water onto fossilized plant mineral dug from the ancient tide-pools of the San Antonio hill country. This traditional method of cleaning rids the specimen of dirt, while also speeding up natural erosion and decay, the same process that had given it its original form. A sense of inevitable annihilation or mutation of matter seems to run throughout his work, but it is often tempered by poetically selected moments of stasis, bringing to mind a line from Plato’s Timaeus: time is “a moving image of eternity”. A similar idea factors into Kurian’s nuclear ‘rocks’, a hardened plastic that contains traces of nuclear waste, short-circuiting the thousands of years it would take for the waste to decompose on its own. For both of these artists, time is something that is shortened, lengthened, made consumable, jerked from underneath you or felt to be expansive, all through slight and subtle manipulations of a material thing.

Jessica Rath’s porcelain sculptures are based on one of the oldest species of edible apples still existing. This particular set references the politicized nature of food production, shaped by human desire, and its sometimes devastating effects to a local ecology. Slavs and Tatars investigate the hybridized language and politics of Eurasia, the geographic area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Wall of China. The group offers a variation of collapsing time, in that a whole history of cultural interchange and interpretation can be embodied in a single, sleight-of-hand work. Spoonerisms, religious goofs, sociolinguistic slips of the tongue, all bring to light both information and mis-information in a collective cultural make-up. A version of this can be found in When in Rome, a puzzle of hi- and low-brow references with a gesture to mis-remembered gypsy culture. This is not unlike Bjorn Copeland’s modified “Associated Grocery” posters - Copeland makes a very simple modification to the signs, but the result is a twisted visual-linguistic gestalt that solicits a little investigation from the viewer. Throwing confusion into the mix can be a helpful tactic for artist and scientist alike – “Nothing whets the intelligence more than a passionate suspicion, and nothing develops all the faculties of an immature mind more than a trail running away into the dark”.

Attempting to understand the fundamental principles of the universe is a very human thing, and it requires a sense of play. Kal Spelletich does it with “a little smoke and mirrors” and the help of machine inventions. These maquettes are activated either by blowing into a breathalyzer, which requires a small amount of alcohol on the breath, or a sign of bodily stress tested through a lie-detector. Spelletich inadvertently points out that these tools have been held for years as accurate, but they may be no less of a pseudoscience than his time and light-wave measuring machines. Sharing in a similar imaginative low-tech approach, Matt Heckert’s flamethrower is a do it-yourself creation from the annals of RE/Search magazine by V. Vale. Heckert likes to create responsiveness in a simple machine, rather than through a super-powerful microchip. Daria Martin’s Soft Materials is also structured around the research of ‘embodied artificial intelligence’: AI that is programmed to function through sensory experience (touching, bumping into things) rather than through a ‘computer brain’. Man and woman engage in a sensual mimetic dance with their mechanical counterparts, studying the kinesthesis of their own bodies through that of another.

Martin may distance her film quite far from the experiment, which was shot on site at a lab at the University of Zurich, but the ghost of the idea remains: the work operates with a leakage between the laboratory, the dance, and the film. For Martin, the way in which one sense triggers another is somehow related to the challenge of trying to translate one medium into an unrelated one. Quoting this idea again in her later work, Martin starts with a real-life experiment of mirror-touch synesthesia, a neurological condition that causes a patient to experience the feeling of being touched when an outside object is stimulated. The single stimulus activates two distinct and unrelated cortical areas of the brain – the sense of sight, and the sense of touch. Although speculative, it isn’t too far off to imagine that both the experience of art and science are somehow equally ‘sensed’.

Ken Johnson for New York Times Review of Weird Science at Jack Hanley Gallery, 2013