Elizabeth Jaeger in Mousse Magazine

Elena Tavecchia Review of The Whitney's Mirror Cells Exhibition

At the core of the group exhibition “Mirror Cells”, curated by Christopher Y. Lew and Jane Panetta at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, are two primary concepts. One is what gives the show its title, the mirror neurons, a new set of brain cells discovered in 1992 by a group of Italian scientists observing macaque monkeys. The discovery shed light on how we understand others and confirmed the essential role of repetition in the interpretation of other people’s actions and intentions, as in the case of empathy.

The auxiliary concept of Umwelt, introduced by the German biologist Jakob von Uexküll in the mid-1950s, explains how different creatures that may be living in the same environment can be focused solely on those elements that are instrumental to their own survival. The example of the tick that shares the same space with the mammal that unknowingly hosts it illustrates how the tiny blind parasite relies only on its sense of touch and the smell of the acids emanating from the follicles for orientation. It has a completely different experience of reality from its host.

We could try a similar experiment in looking at the perceptions of reality of the artists in the show. The eighth floor of the Whitney Museum is covered with a gray carpet, yet this uniform surface can be interpreted in a completely different manner according to each artist’s approach and their works on display.

In the context of the works by Maggie Lee, the carpet evokes a domestic setting. The New York–based artist extracted four chapters from her video Mommy (2015), one for each member of the family, and presents each with a personalized display: the magician father who left them when she was very young, the punk older sister, the tragedy of her mother, who immigrated from Taiwan in the early 1970s and died unexpectedly, and the artist herself. Lee combines personal content with found images and mounting techniques, blurring the boundary between the intimate and the public dimensions.

The same floor surface becomes a stage where the Los Angeles sculptor Liz Craft displays her unsteady papier-mâché mannequins. The characters are women with fashionable clothes and hairstyles, and their standing balance is maintained by spiderwebs of tied strings departing from their heads or body joints and connecting them to the floor and the wall. The mannequins are not moving, but their uncanny expressions combined with ceramic mouths and dialogue bubbles scattered around the walls suggest a surreal communication among them.

Rochelle Goldberg’s rhizomatic display is taking place on the same carpet, which here turns into soil. An irregular patch of chia seeds is sprouting, and it describes the perimeter of the installation, which also includes ceramic pelicans, suitcases, a human face, and metal structures. The organic, shining forms of the snake-patterned ceramics are counterbalanced by the rigid metal frames, which address the architecture of the space. Goldberg’s dystopian landscape, with its ambiguous intersection of animate and inanimate organisms, evokes environmental precariousness.

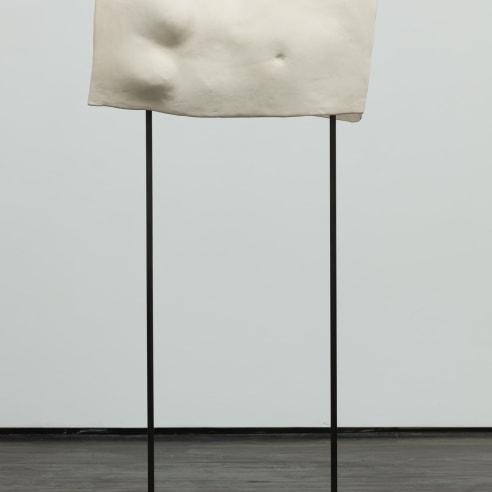

The soft quality of the carpet is a stabilizing ground for Elizabeth Jaeger’s black ceramic vessels, which are supported by metal sawhorses. Although very similar, each piece has a distinct form and some are intentionally cracked. What seems at first a bold appearance is diminished by the minimal depth of the work when it is viewed in the round; we realize that they are actually useless containers. Jaeger intends the work to evoke personal narratives; its title refers to her grandfather, who suffers from the gradual mental decay of dementia.

Win McCarthy’s white frames reflect the neutrality and alienation of the monochrome carpet. His maquettes re-create spaces inside the space, where the uneasiness of urban life is combined with distorted versions of the artist’s previous exhibitions and personal memories. The city of New York is constantly evoked through photographs of its skyline, while cutouts of newspapers with weather forecasts, recent events, and recent dates are combined with the artist’s poetry describing daily scenarios and anxieties.

Rather than empathizing (one of the most direct implications of the mirror neurons discovery), the works in “Mirror Cells” do not relate to each other directly through repetition or imitation. But some common elements are discernible. What characterizes all of them is a process-based approach whereby the artist is directly involved with the work, either physically or emotionally, in contrast with digitally based works that are predicated on advanced technologies and anonymity. The medium of ceramics is shared by Craft, Goldberg, and Jaeger, and although each artist develops it in a different direction, the experience of determining the shape, color, and texture of this material stimulates an attention to tactility on the part of the viewer. The density of the installation is perhaps the most consistent element of the show; the display of works all over the floor, walls (including a hidden white eagle on the high beams by Goldberg), main corridor, window, café, and terrace make it an experience that engages the museum in its entirety.